Galapagos Conservancy has been supporting the Association of Interpretive Guides of the Galapagos National Park (AGUIPA) since 2022 to deliver the “Synergy For Well-Being And Conservation” project, led by environmental education specialist Yanex Alvarez. This project is aimed at integrating art, science and conservation to promote the well-being of children and youth in Galapagos.

Creative Science Workshops

Public Library of Puerto Ayora is the organization that brings this project to Galapagos’ youth. The project’s creative science workshops are one of its most noteworthy components. The workshops are intended to spark an interest in science concepts in children through hands-on and playful activities, thereby increasing environmental awareness. In a workshop on the El Nino, for example, children are asked to simulate temperature changes in water. They can then observe the impact of this climatic phenomenon on different parts of the globe, including Galapagos.

Field Trips

The educational program is not complete without field trips. Santa Cruz Island’s highlands offer children the chance to learn about biodiversity and the natural environment while promoting creativity and active learning. These outdoor experiences can also improve emotional wellbeing. A study of giant turtles is a good example. Children gain a new perspective on life by watching the tortoises in their natural habitat.

Bird watching and artistic workshops

Children can learn about Galapagos’ biodiversity by combining bird watching with artistic activities, such as painting and drawing the birds they observe. The participants are provided with notebooks and binoculars to learn how to identify and record different bird species. It helps them to improve their observational skills and develop a greater appreciation for wildlife.

©Galapagos Conservancy

Our Commitment to Education

We are pleased to be able to collaborate with the community via the Public Library where many educational events take place. We believe education is essential for long-term conservation, and we are committed to providing resources and support in order to continue the success of the program.

Washington Tapia is our General Director. He notes that AGUIPA’s educational project does not only train future conservationists in Galapagos, but also creates a model of innovative education that combines art, science, and environmental awareness. He said that by providing enriching educational experiences to children, AGUIPA contributes to the holistic development and commitment of future generations.

People like you, who care about the conservation and wellbeing of Galapagos, make it possible to support initiatives such as this. Your support allows projects like this to be implemented. Together, we will ensure that the children of today become the environmental guardians, prepared to face challenges with creativity and passion. Galapagos conservancy will continue to support this vital initiative, working with the community in order to preserve Galapagos, its wonders, and future generations.

Photo: ©Galapagos Conservancy

The Galapagos Islands, unlike many other areas, do not follow traditional seasonal patterns. Instead, they experience two distinct seasons, the warm, wet and humid season, which runs from December to April, and the cool, dry and windy season, which runs from June to November. The ocean currents that surround the islands play an important role in the climate and wildlife of the archipelago.

The Warm Season and Cool Season

The warm season can bring out the best in the archipelago. The landscape is covered in clear skies, radiant sunlight and temperatures between 25degC to 30degC. Warming waters are ideal for water activities like diving and snorkeling to see the marine life that is thriving, such as colorful tropical fish, majestic turtles and fascinating sharks. The vegetation on land is nourished and flourishes by torrential rainfall, which provides ideal breeding conditions for a variety of birds and terrestrial creatures. Visitors can also enjoy the opportunity to see terrestrial wildlife in its peak activity.

The cool and dry seasons are characterized by a slightly cooler climate and a more variable weather pattern. This period, also known as “dry season” and “garua,” is marked by fog or drizzle on the higher parts of the islands that alternates with clearer skies along the coast. The average daytime temperature is 23degC, with August as the coolest month. The waters are cooler than in the summer, but they are still nutrient rich, which attracts a wide variety of marine animals, including whales and dolphins. The Galapagos Islands are also more peaceful and less crowded during this season, which allows you to enjoy the abundant marine and terrestrial wildlife.

Photo: ©Galápagos Conservancy

Impact of seasonal changes on conservation efforts

Dr. Michael S. Dr. S. has a lot of important information about the impact of seasonal variation on conservation efforts in the archipelago. Dr. Jorge Carrion is the Director of Conservation for Galapagos Conservancy. He highlights that while the warm season promotes reproduction, it also coincides with increased tourism. Tourism must be managed in a way that protects breeding animals.

The seasons also have a direct impact on the planning of conservation efforts and expeditions. The climatic conditions are taken into consideration when park rangers, conservation authorities, and scientists perform ecological monitoring. This ensures the effectiveness of conservation operations in helping to mitigate human impacts on ecosystems throughout the year.

Galapagos: The resilience of life

Galapagos’s dramatic seasonal changes are a testament to its unique flora, and the adaptability and resilience of the island. Galapagos’ species are able to adapt to its changing climatic conditions and environmental challenges. We can contribute to the conservation and protection of the Galapagos Archipelago by recognizing the seasonal variations that affect many species, and the patterns of tourism.

Photo: ©Galápagos Conservancy

The Board of Directors of Galapagos Conservation (GC) toured the Galapagos Islands in order to assess the effects and progress of conservation projects that were funded and implemented by this organization. The Board of Directors of Galapagos Conservancy (GC) visited the Galapagos Islands to evaluate the progress and effects of conservation projects funded and implemented by the organization.

The visit included meetings with partner organizations. One meeting was held at the Galapagos National Park Directorate to review the progress, success, and future needs for projects funded by GC and managed by DPNG. The partners reaffirmed that they would work closely with the park rangers in order to contribute to the recovery and survival of Galapagos’ threatened species.

The board also conducted a protocol to the Charles Darwin Foundation with whom GC is currently cooperating through a major grant project for a monitoring marine ecosystem. The Charles Darwin Foundation invited the GC Board to its research station. They also gave a brief overview of the marine project funded by CDF and showed them the impressive collections of plants and vertebrates. GC Board Members, many of whom were new to the organization appreciated the chance to learn more and expand the partnership with the Charles Darwin Foundation.

During the visit, Board Members also toured the Agency for the Regulation and Control of Biosecurity and Quarantine for Galapagos. They were impressed by Galapagos Conservancy ‘s commitment to helping ABG control and eliminate invasive species. GC Board Members fully understand the importance of ABG’s initiative and support it. Jean-Pierre Cadena (ABG’s Executive director) highlighted the importance of Galapagos Conservancy actively participating in the fight against invasive species.

Photo: ©ABG

The Board’s active participation in the second Conservation Actions Fair was another highlight of their visit. The Galapagos Conservancy funded many community projects at this event. The fair featured booths operated by a variety of beneficiaries, such as male and female entrepreneurs and partner institutions, like the Galapagos National Park Directorate and the Agency for the Regulation and Control of Biosecurity and Quarantine for Galapagos. The fair featured a cultural show featuring local artists that strengthened the attendees’ commitment to protect and promote sustainable development in Galapagos.

The Board visited Floreana island, where they learned about the efforts being made to eradicate rats and cats on the island. This is in preparation for the introduction of Giant Tortoises as part of GC’s Iniciativa Galapagos Program next year. The Board met with the first WISE awardee on the island. This island has approximately 150 residents, and 30 students and adolescents. The project involves the establishment of the first public library on the island, and was made possible by donations from Board members.

Photo: ©Galápagos Conservancy

Since its founding in 1985, Galapagos Conservancy is dedicated exclusively to the protection of the Galapagos Islands. Every two years, the Board of Directors travels to Galapagos to evaluate and monitor conservation efforts. Dr. Dan Sherman emphasized that we are proud to work closely with our partners and support the implementation of local conservation efforts. He also reaffirmed his commitment to work towards the recovery and restoration of habitats, as well as the development of sustainable Galapagos communities.

Conservation: A 39-Year Commitment

©Galápagos Conservancy

Since Galapagos Conservancy was founded in 1989, it has worked to conserve this unique biodiversity and ecological jewel. Our donors and conservationists have been a great help in our efforts to protect Galapagos’ ecosystems. We are able to implement vital initiatives on the island thanks to their contributions. We acknowledge the efforts of the local communities, who have demonstrated their commitment to Galapagos by participating in various conservation initiatives and enterprises.

Our Director of Conservation Dr. Jorge Carrion explains that “constant effort, well-planned conservation action, community support, and donations from individuals committed to Galapagos are essential for continuing to implement measures that contribute towards safeguarding Galapagos unique ecosystems.” We can protect species that are found nowhere else in the world thanks to their support.

Galapagos: A future where it thrives

We are an organization that focuses on creating a sustainable future in Galapagos. We strive to protect its ecosystems and improve the lives of its inhabitants. We are proud to be working hand-in-hand with our main partner, the Galapagos National Park Directorate. This organization has a team highly trained park rangers who tirelessly work to protect Galapagos’ biodiversity.

©Galápagos Conservancy

“Our commitment is that we will continue to fight for conservation on Galapagos, and continue to contribute so future generations can continue to enjoy the natural wonders in the archipelago,” Dr. Carrion says.

We congratulate Galapagos National Park Directorate on this World Environment Day for the hard work they do to protect this natural heritage every day. We invite the entire world to join our efforts to protect the Galapagos Archipelago, and by extension the planet. We can all make a positive contribution to the environment in our everyday lives, particularly in places such as the Galapagos Islands. Simple actions can include using reusable containers and bags, managing water and electricity in the home, avoiding consumption, and buying products from companies that have sustainable and ethical business practices. These simple everyday actions are beneficial to our local environment, and they contribute to the health of the Galapagos ecosystems and its unique species.

Shared Responsibility

World Environment Day is a reminder of the importance of conserving and protecting our planet for future generations. Galapagos Conservancy is firmly committed in its efforts to conserve the Galapagos eco-systems and their unique biodiversity. We recognize that every individual can contribute valuable contributions in this effort, says Dr. Carrion.

Join us on this mission. Happy World Environment Day.

©Galápagos Conservancy

The Galápagos Conservancy’s Conservation Center in Puerto Ayora, Santa Cruz Island will soon undergo a thorough renovation. Since its opening in June 2022, the center has become a valuable source of information about the Galapagos, especially regarding the history and conservation efforts aimed at the most iconic species of the Galápagos, such as our giant tortoises.

Regular visits from local residents over the last two years have been a defining feature. They come to the center to learn about conservation projects and understand the importance of conserving their home, the Galápagos. The frequent visits from children and students are particularly heartening, as their enthusiasm and questions help nurture the next generation of nature enthusiasts.

Our spectacular 3D map of the Galápagos archipelago is a major attraction for both national and international tourists. Upon each island is depicted an intricate rendition of each of the 15 species of Galápagos tortoises – wooden masterpieces crafted by a local artist, showcasing our dedication to providing a space for knowledge and learning.

As we move forward, we are actively updating the conservation and sustainability information for the upcoming renovated Conservation Center. Our goal is to meet current expectations and needs for information about Galapagos. During this time, the Center will undergo a temporary closure.

We are looking forward to the opening of a newly renovated Galápagos Conservancy Conservation Center later this year. The center will have improved infrastructure and updated information, and we aim to continue sharing our work and advocating for the care and conservation of this global natural heritage.

©Galápagos Conservancy

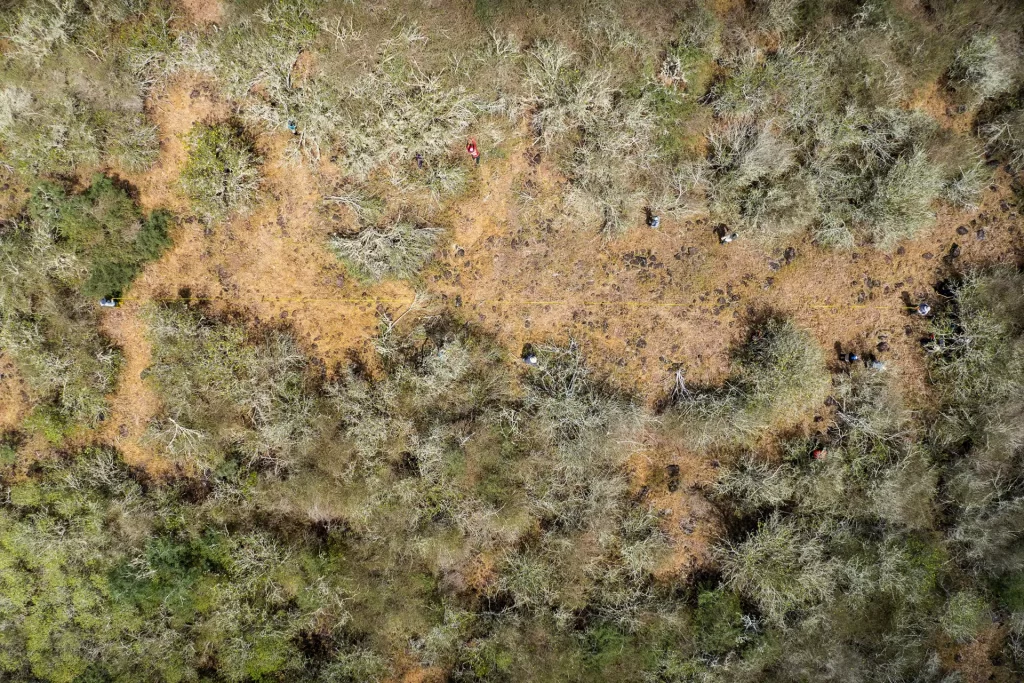

The recent field mission in the stunning Espanola island, located in the southeast sector of the Galapagos Archipelago, brought together a team consisting of 27 Galapagos Park Directorate Rangers and Conservation Officers from Galapagos Conservancy who were working to improve nesting habitats for the waved Albatross. This majestic seabird is unique to the Galapagos and nests only on Espanola Island. Thousands of tourists flock to this island every year to see the mating rituals.

Focus and development of the Expedition

The recent expedition was an important step in our efforts to protect waved albatross. We work closely with the Galapagos National Park Directorate to implement conservation measures aimed at restoring ecosystems on the island and allowing its unique biodiversity to flourish once again.

©Galápagos Conservancy

The mission was aimed at clearing “runways” for these birds to take off and land. The vegetation on the island, which has grown overgrown over the past few decades, is a barrier for these birds with 6 foot-long wingspan to reach their nesting area on the Island. The team worked under the scorching sun for ten days before the albatross arrived to nest on this beautiful, yet arid island. They cleared forty-nine runways measuring 33 feet by 164 foot, removing obstacles that could threaten the safety and flight of the birds. It was not an easy expedition. The daily hikes were up to 7.5 mile over rocky terrain, and the work of removing shrubs from nesting areas was demanding. The majority of trees that were removed were “muyuyo”, or Cordia lata, a species native to Ecuador and Polynesia. It has been invading the island ever since the collapsed population of the endemic giant turtle, which used to maintain open areas where albatross could nest.

Impact and Future Plans

©Galápagos Conservancy

Our conservation director Dr. Carrion says, “It’s essential to protect the integrity of albatrosses at their only nesting site in the entire world.” Jorge Carrion has seen first-hand the positive effects of these conservation efforts on the albatross populations.

Our focus will remain on the strategic conservation actions of Galapagos Albatrosses. We plan to return to Espanola Island later this year, to maintain the runways for these iconic birds and to monitor the status of the tortoises who were returned in the previous months.

Commitment to conservation

Our conservation expeditions demonstrate our commitment to protecting the unique biodiversity of Galapagos. We will work tirelessly to ensure the future of the waved albatross, as well as all the other natural wonders which make the Galapagos Islands so special.

©Galápagos Conservancy